It is rare for much time to pass without a new front being opened by anti-smoking crusaders. This month has seen a particularly high level of activity. Legislation dictating that tobacco products, Lucky Strike cigarettes and advertisements will have to be kept out of sight in shops from next July was passed with the support of all but three Act MPs.

It is rare for much time to pass without a new front being opened by anti-smoking crusaders. This month has seen a particularly high level of activity. Legislation dictating that tobacco products, Lucky Strike cigarettes and advertisements will have to be kept out of sight in shops from next July was passed with the support of all but three Act MPs.

Not to be outdone, George Wood, the chairman of the Auckland Council’s community safety forum, proposed a ban on smoking in inner-city streets. Then, most astonishingly, the Auckland District Health Board said it was looking at refusing to hire smokers.

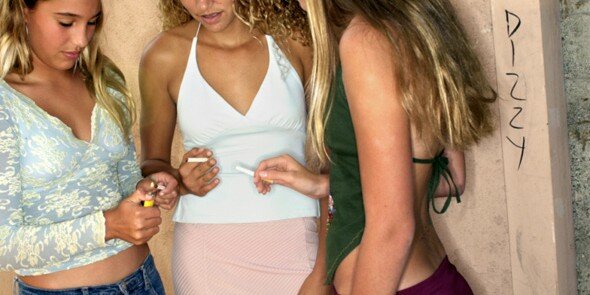

All these initiatives highlight the pressure on policymakers not only from anti-smoking lobbyists but from a community that has rapidly come to vilify the practice. People once enjoying an acceptable pastime now find themselves literally out in the cold. A wide range of measures have been used to drive that message home, yet about 20 per cent of people continue to light up. Thus new means to persuade that stubborn minority to quit keep being proposed.

To their credit, some policymakers have recognised that some of these suggestions are, quite simply, a step too far.

They acknowledge what many anti-smoking advocates do not – that smoking is a legal pastime enjoyed by a significant number of people, and that their rights must be balanced against other people’s protection from secondhand smoke.

Such was the case when Mr Wood’s plan to have smokers banned from gathering in front of inner-city buildings was rejected. The spectacle of smokers huddling together outside workplaces is certainly unappealing. But if this were denied them, it is reasonable to ask where would they smoke. And if this were the home or the family car, how long before anti-smoking lobbyists would be trying to dictate what happens in these places, even though this is generally considered the individual’s own business?

More questionable still is the Auckland District Health Board’s proposal to refuse to hire smokers, an approach which is said to recognise the responsibility of doctors and nurses “to be positive role models in dealing with patients and the public”. Logically, that means obese people will also not be hired. Like smokers, they hardly fit the health and wellbeing ideal that the board seems to think its staff should embody.

All this posturing by pressured policymakers is largely a waste of time, effort and money. Their initiatives are likely to be no more successful than most of those tried over the past few years – the likes of education campaigns, smoke-free areas, subsidised quit programmes, graphic health warnings on cigarette packets and restrictions on the promotion of tobacco and, now, the display of tobacco products. All have had public support and have been accepted with resignation by smokers. But while the dangers of the practice have been rammed home time and again, a fifth of people still light up.

A wealth of research has shown that, in reality, the best way to reduce the number of smokers is by hiking the cost. Since the turn of the century, however, the tax on tobacco has been raised just twice, once in 2000 and again last year at the behest of Associate Health Minister Tariana Turia. Increased prices are a particular deterrent to youngsters.

New Zealand, however, has failed to acknowledge the effectiveness of this approach, and its excise and sales tax, as a percentage of the retail price of tobacco, is well below that of most comparable jurisdictions. Therein lies the answer for those who want to make the country smoke-free by 2025. Other solutions touted by anti-smoking groups smack of extreme and, ultimately, fruitless fiddling.